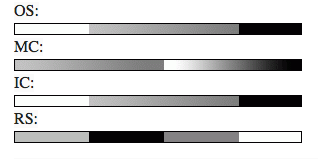

Many of the story analyses on the site have diagrams at the bottom labeled “Plot Progression Visualizations/ Dynamic Act Schematics”. They seem to visually describe the story’s OS, MC, IC and RS throughlines within the 4 act structure. But beyond that I don’t understand the significance of their shading/gradation patterns and the meaning of the various separations. Or what value this visualization is. Why are some acknowledging each signpost? Why are some shading through a signpost without a clear division. Can someone explain?

In the example shown above, why are OS and IC identical in form? What is the significance of that? What is the significance of the darker areas being near the end on the OS, MC and IC? Yet why is OS and IC fully shaded on the fourth act vs. the MC merely gradates to black near the end? Why is there clear separation on MC between SP 2 & 3 whereas on OS and IC the separation is between SP 1 & 2 and 3 & 4? Yet with the RS, the clear separations are at every signpost. Why? I realize the particular storyform this was generated from created these patterns, but generally what do all these subtleties, and relationships between them and the structure, mean? What in the story form is causing the visualization characteristics? How could this type of visualization help a writer, analyzer distinguish a storyform?

I generally get the idea of them, but I haven’t really done too much work with them yet. If you go to

I generally get the idea of them, but I haven’t really done too much work with them yet. If you go to