Is the MC P/S/F/D tied to his character as opposed to a subplot?

I came across this post, listing the Problem/Solution/Focus/Direction as part of the characteristics section of Dramatica, tying it to a general ‘type’

Further on in the post, I found @kf27 had organized it by character-trope/ character ‘genre’ so to speak

So as I wrestle over identifying quads and issues for my story, should I keep the MC as a character related issue? I’m learning Dramatica as a spiral, and am back to the domain level, wondering if I’m mixing my protagonist’s goal with the MC issue. I cannot easily separate them.

Related, is the MC issue internal? Or is it just a side-plot?

Here are details:

OS: Dystopia, centered over a prejudice against a certain people, trying to make the future right again after those people messed up the world. Interdiction is somewhere in this. The Trilogy OS characters are involved in a social system that is cleaning up society. But in the first book, that system doesn’t show up directly until act 2. In act one, the Protagonist is making her way to the city.

MC: She is left alone when her family is taken as part of the clean up. She doesn’t want to rescue them (too big of a job, too big of an enemy), but to stay safe until…she is guilted into helping them/ pushed in to find them.

End: Good. But she doesn’t find them (yet). Instead, she is in a safe-for-now place.

Not sure if she succeeds at the goal, because the goal is to be safe but also to find her family. The OS people are working at cleaning up society, so her family’s arrest is part of that.

But also, the MC has issues she is dealing with besides being alone. Doubt and fear. All the while, we have a Trilogy storyform going on overhead.

With all this ‘obtaining’ it seems like we are OS Future/Obtaining. But with the interdiction, making up for the past, it seems like maybe OS Past/Interdiction.

If that’s the case, and OS Interdiction,

Which works, because she is a math person, always calculating, trying to think her way out of the problem of inequity. This would mean Characteristics as @Gernot listed them is the key to decoding the MC issue. (@jhull which may help improve subtext)

But is that, then, the UA instead of the problem?

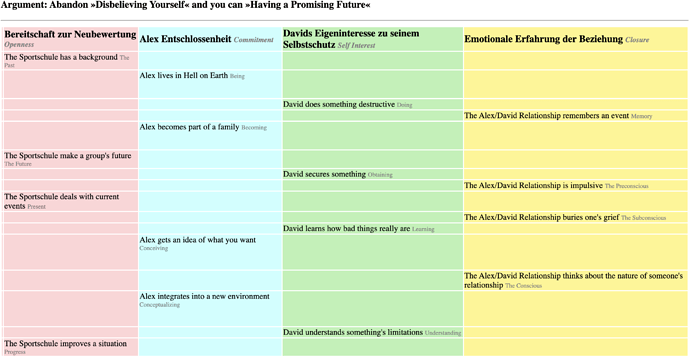

When I set up this storyform on Dramatica/Subtxt, I get the following premise:

Virtuous are those who keep focusing on how the outside world is letting others know they are not desirable (Character : DESIRE) even if it means being forgotten by a group (Plot: MEMORY)

I’d say, “Yay! I found it,” because in truth Memory is the thing she is trying to avoid…

Except…

…I have made about twenty storyforms (or more) over the past years of trying to identify this story’s elements,

…and each time it felt right.

…And each time i outlined the story accordingly, spending hours on thinking it through,

…and each time I hit a brick wall. (documented on discuss.dramatica by my questions over the years)

Any advice would be appreciated.

%

%