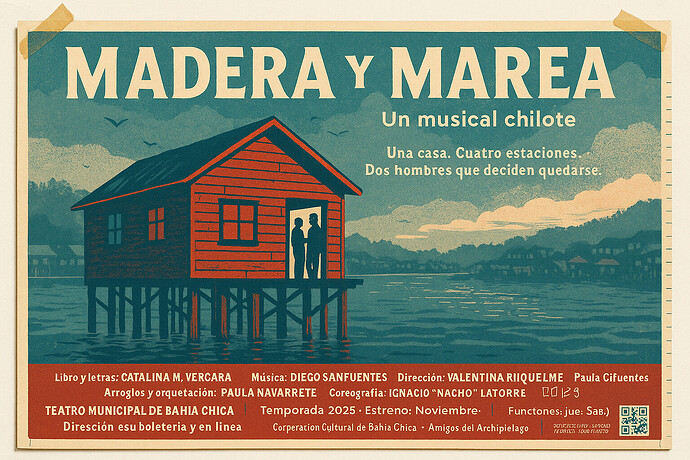

And then, finally, our Chilean musical:

Madera y Marea

In Castro, where stilted palafitos bite into the tide like teeth, a will lands on a wooden table. Two names in careful ink: Tomás and Rafael. The house sits on posts at the waterline, shingles scabbed with salt, kitchen leaning like a shoulder after a hard day. The clause is simple and stubborn: live here together for four seasons, restore the palafito to code, sell only if both agree. Tomás smells of rope and diesel; he dives for mussels at dawn and patches hulls by noon. Rafael steps off the bus from Santiago with knives wrapped in linen and an apron folded like a letter. The two men sign, each gripping the pen as if it were an oar.

Their first days are all creaks and boundaries. They chalk a line down the plank floor—his side, his side—then erase it because the stove sits in the middle, and nobody can cook on rules. The house lists with the tide; barnacles grip the posts; rain needles the windows. Tomás stacks jacks under sagging beams, shoulders a length of alerce reclaimed from a collapsed shed, and swings a hammer until his palms blister. He talks with his hands, not his throat. Rafael inventories the pantry, lays out jars of chilote potatoes, scrubs a rusted oven until it shines, and coaxes a stock to life that smells like fog and fennel. He curates memories as if they were dishes, and plates the town’s stories with a steady hand.

Around them, the town names and sorts. A preservation activist, Doña Elvira, circles in a wool shawl and a fixed smile, guarding a notion of “authentic” that stops at their doorstep. “This street is for postcards,” she says, tapping a post as if it were a drumhead. A flipper, Iván, idles his truck by the water and flicks a business card through the air—cash now, no waiting, no inspection. The choir of neighbors watches from balconies: fishermen with nets like wedding veils, a clerk eating sopaipillas from a greasy paper, cousins on a stoop who whisper and grin. Labels collect like kelp on a rope: roommates? partners? from here? from away?

Winter presses in. A king tide rises, green and patient. The floor lifts, the nails sigh, and cold water licks the boards. Tomás bolts with a jack and a beam, his jaw tight; Rafael lifts the stove with him, hands under iron, teeth bared. They don’t talk; they grunt, brace, lift, and the house settles by a hair. Later, with socks steaming on a chair back, they eat in silence, shoulders touching because there’s only one dry chair. The closeness is accidental and immediate. A laugh slips out; it smells like broth and smoke. The tide falls back, the house breathes, and the two men watch the posts drip in the moonlight.

Spring brings light and a checklist. Permits, inspections, a ledger with costs in red ink. Doña Elvira posts flyers for a “pure” festival that frames tradition like a bell jar; Rafael frowns, then drafts a community meal that folds queer couples and widowed elders into one long table. He calls it a registry of taste, and he puts names to recipes in chalk. Tomás hates the chalk and the attention, but he planes plank after plank in the back room, shavings falling like pale petals. Their work rhythms clash and then click. In the afternoon, Rafael’s knife taps a board—finely, lightly—and Tomás hammers until the head of the nail kisses the grain. At night, when the foghorn groans, they count rib bones through a thin shirt and look away. Attraction runs like a current under a dock: felt, not discussed.

The flipper returns with smarter math, an easier line: one signature, one payout, one clean exit. The house would go to tourists with white sneakers and phones. Tomás shakes his head and rolls his shoulders. “We finish what we start.” Rafael darts his eyes to the mainland, where a friend texts a job offer with a glossy kitchen and a view of the Andes. He pockets the phone, then lingers by the window where a damp breeze licks his wrist.

In the attic, tucked in a beam, they find a letter wrapped in waxed cloth. Ink faded to tea. Two men with initials and a map to a cove where they met under a threaded sky. “We couldn’t live here together, but this house kept our things,” it reads in a cramped hand. The house holds more than beams; it holds a pattern. Tomás swallows, tastes salt. Rafael rubs the folded paper, sees grease bloom at the crease. They put the letter back where they found it, then look at each other as if they’ve been introduced again by ghosts.

Summer puts color on the shingles. They hang tejuelas like fish scales, dark and gleaming, each nail a small decision. The tourist boats drift past, cameras up; Rafael opens the kitchen door and feeds whoever climbs the steps—boatmen with rough palms, a young couple with sand on their ankles, a shy boy who asks if two men can run a house together like a boat. Tomás sands a rail until it glasses under his touch, then answers the boy with a nod and a “sí” that settles like a pebble in a jar. The activist frowns from the pier, and the town inspector joins her with a clipboard and a careful cough. “Delay,” he says, pointing at a post. “Delay,” she echoes, nodding at their joined work.

Work bites their ankles. Schedules pile. Tomás takes rescue runs when a skiff calls mayday, drags heavy bodies out of gray water, and comes home late, doubts clinging like weed. Rafael burns a sauce when a group argues in the doorway about who gets to sit near the window, and he slams the pot in the sink hard enough to spray his chest. They snap at each other; then they fix a hinge together without a word. Each time they make a rule to keep the peace, life bends it like a wet oar.